ASTRO SPACE NEWS

A DIVISION OF MID NORTH COAST ASTRONOMY (NSW)

(ASTRO) DAVE RENEKE

SPACE WRITER - MEDIA PERSONALITY - SCIENCE CORRESPONDENT ABC/COMMERCIAL RADIO - LECTURER - ASTRONOMY OUTREACH PROGRAMS - ASTRONOMY TOUR GUIDE - TELESCOPE SALES/SERVICE/LESSONS - MID NORTH COAST ASTRONOMY GROUP (Est. 2002) Enquiries: (02) 6585 2260 Mobile: 0400 636 363 Email: davereneke@gmail.com

Why a Seestar Telescope Should Be Your First Choice

Every now and then, a piece of technology comes along that doesn't just improve what we do—it reshapes the entire experience. For us, that moment arrived when ZWO generously donated a Seestar telescope. Since then, our public night-viewing sessions have been transformed. This compact, self-contained smart telescope has become the centrepiece of every stargazing event we run, drawing crowds, sparking curiosity, and giving first-timers the thrill of capturing real astronomical images in minutes.

The Seestar range—especially the S50 and its smaller sibling, the NEW S30—has done something rare in amateur astronomy. It has removed almost every barrier that traditionally stops newcomers from getting involved. No fiddly collimation. No heavy mounts. No weeks spent learning cables, cameras, and calibration frames. Instead, you open the case, place it on its tripod, tap a few icons on your phone, and within moments you're watching deep-sky objects reveal themselves in crisp, colourful detail. For pure ease of use, nothing else in its class comes close!

What has surprised us most is how quickly people of all ages take to it. Kids, retirees, curious first-timers—everyone wants a turn. The software guides you, the focusing is automatic, and the telescope aligns itself without any drama. The result: sharp, professional-looking images of galaxies, nebulae, clusters, and the Moon, captured with minimal effort and at a cost that's genuinely accessible compared to traditional astrophotography setups.

It has changed the way we run astronomy events. Instead of struggling with big gear or racing to troubleshoot something in the dark, we're free to share the stories behind the stars. The audience gets a front-row seat to the universe without the wait, and we get to spend more time connecting people with the night sky. On a personal note, the Seestar has reignited my own passion for capturing the heavens.

\More than once I've found myself outside at 2 a.m., watching the latest image build on the screen, amazed at what this little unit can pull out of the darkness. I've even taken it overseas to Norfolk Island on our annual Astro Tours, where it performed flawlessly—light, portable, and rugged enough to handle the travel. That combination of performance, portability, and price is why I recommend the Seestar S50—or the S30 for those who prefer an even more compact option. It suits beginners, it impresses seasoned observers, and it delivers high-quality results without the steep learning curve normally associated with astrophotography.

NEW MODEL RELEASED: ZWO announced their new Seestar S30 Pro Smart Telescope a few months ago at the NEAF show in the USA. They've since added some additional features including the ability to capture wide-field Milky Way portraits and star trails. Combined with camera upgrades to allow for 8K imaging, advanced planning mode, along with daytime scenery, nature and bird photography capabilities, we think this new offering from ZWO is going to delight many astronomy and nature fans.

If you've ever dreamed of capturing your own images of the universe, or want to give someone a gift that inspires excitement long after the holidays, this is the one. The Seestar has earned its place as one of the most exciting, accessible instruments ever made for amateur astronomers. SEESTAR WEBSITE: https://www.seestar.com/ Your Australian retailer BINTEL: https://bintel.com.au

HERE (Below) IS A SE LECTION OF IMAGES I'VE TAKEN FROM OUR SUBURBAN LOCATION WAUCHOPE NSW (Bortle 3)

Cool Space Events You Won't Want to Miss in 2026

The year 2026 is shaping up as a standout for space watchers. From dramatic meteor showers and rare eclipses to a historic crewed mission around the Moon, the coming months offer a steady parade of cosmic events that are easy to follow and, in many cases, easy to see. Here's what's ahead — and why it matters.

A Historic Moon Mission With a Canadian Onboard

One of the biggest milestones of 2026 is NASA's Artemis II mission, the first crewed voyage back toward the Moon since the Apollo era.

Four astronauts will fly aboard the Orion spacecraft: Reid Wiseman, Christina Koch, Victor Glover, and Canadian astronaut Jeremy Hansen. Unlike Apollo, this mission will not land. Instead, it will orbit the Moon once, testing systems and procedures needed for future lunar landings.

The mission is expected to last about 10 days, with a launch window opening in early February. When the spacecraft swings around the Moon, the crew will travel farther from Earth than any humans ever have — even surpassing the record set by Apollo 13 in 1970. For Canada, this is a historic first: the first Canadian to travel to the Moon.

Meteor Showers Worth Setting Alarms For

Meteor showers remain the most accessible space events of the year — no telescope required.

-

Quadrantids

Late December to mid-January

The Quadrantids peak in early January and can produce over 100 meteors per hour. However, in 2026 the peak coincides with a full Moon, which will wash out many of the fainter streaks. It's still worth a look if skies are clear, but patience will be needed. -

Perseids

July 17 to August 24, peak August 12–13

This is the showstopper of 2026. The Perseids can reach up to 150 meteors per hour, and the peak falls during a new Moon, meaning dark skies and excellent visibility. This is one of the best Perseid displays in years. -

Geminids

December 4–17, peak December 13–14

Often considered the most reliable meteor shower, the Geminids return at year's end with another strong performance. The Moon will be a waxing crescent, so moonlight interference will be minimal.

A Year of Eclipses

After a quiet stretch, eclipses return in force in 2026.

-

Total Lunar Eclipse — March 3

A total lunar eclipse will be visible across Canada. Western regions will see the entire event, while eastern areas will catch the eclipse as the Moon sets. During totality, the Moon will turn a deep copper-red colour. -

Partial Solar Eclipse — August 12

While a total solar eclipse will sweep across parts of the Arctic, Greenland, Iceland, and Spain, Canada will experience a partial solar eclipse. Viewers in central and eastern regions will see the Moon take a noticeable "bite" out of the Sun. Proper eye protection will be essential. -

Partial Lunar Eclipse — August 28

Two weeks later, most of the Moon will slip into Earth's shadow, turning it a muted red-orange. This eclipse will be visible across the country.

Robotic Missions to Other Worlds

Beyond Earth's orbit, several major robotic missions are scheduled.

-

Venus Atmospheric Probe (Summer 2026)

Rocket Lab plans to send a probe into Venus's thick atmosphere to search for organic chemistry. This follows earlier studies that reported traces of phosphine — a chemical associated with life on Earth — in Venus's clouds. -

Japan's Martian Moon Exploration Mission

Launching in 2026, this mission will study Mars's moons, Phobos and Deimos, and return a sample from Phobos to Earth — a first for Martian moon exploration. -

Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope

Possibly launching in late 2026, this next-generation space telescope will investigate dark matter and dark energy, mysterious components thought to make up most of the universe. A Year Worth Watching the Sky

Between a crewed Moon mission, exceptional meteor showers, rare eclipses, and ambitious planetary exploration, 2026 offers no shortage of reasons to look up. Some events last minutes, others span months — but all remind us that space is very much alive with activity. Keep your calendar handy, your alarm set, and your eyes on the sky.

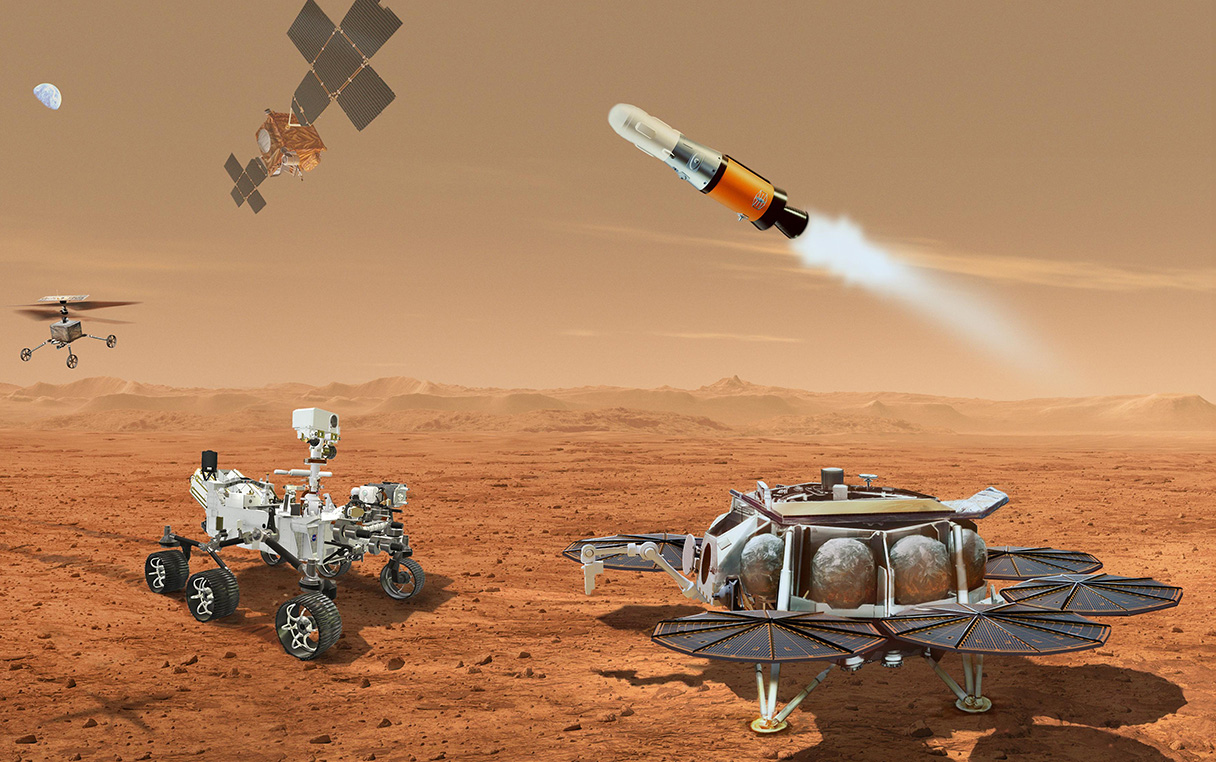

NASA's Mars Sample Return mission is dead

For decades, bringing pieces of Mars back to Earth has been one of planetary science's greatest ambitions. Tiny rocks drilled from another world, returned to Earth and examined in laboratories far more powerful than anything that could ever fly in space. It was a bold vision — and now, that vision has come to an abrupt halt. NASA's Mars Sample Return mission is effectively dead.

The concept began with great promise. NASA's Perseverance rover, which landed on Mars in 2021, has already completed its role. It drilled core samples from Martian rocks, sealed them inside small metal tubes, and carefully placed them on the surface. Those tubes remain on Mars today, waiting.

The trouble came with everything that was supposed to happen next. Returning the samples required an extraordinarily complex chain of missions. A spacecraft would have to land near Perseverance. A small rocket would then launch the samples off the Martian surface — something never done before. An orbiter would capture the container in space, carry it back to Earth, and release it safely without contaminating our planet.

That plan slowly unravelled. Costs spiralled out of control. What began as a mission expected to cost a few billion dollars ballooned to more than $10 billion, with completion dates slipping into the late 2030s or beyond. Technical risks increased, schedules slipped, and confidence inside NASA eroded. Eventually, the agency reached a hard conclusion: the mission had become too expensive, too slow, and too risky to continue in its existing form.

This was not a simple budget trim. It was a strategic decision. NASA is juggling major commitments — returning humans to the Moon, preparing for crewed missions to Mars, monitoring Earth's climate, and exploring the outer solar system. Something had to give, and Mars Sample Return was the most costly and complicated project on the books.

For scientists, the loss is deeply disappointing. Those samples could have answered some of the biggest questions in planetary science:

- Did Mars ever host life?

- How did rocky planets form and evolve?

- Why did Mars become cold and dry while Earth remained habitable?

No rover instruments, no matter how advanced, can match the precision of Earth-based laboratories. Yet the story isn't entirely over. The sample tubes are still safely stored on Mars. They haven't been lost or destroyed. Future missions — perhaps smaller, cheaper, or involving international partners — could still retrieve them one day. Many researchers believe the idea will return, reshaped by new technology and more realistic budgets.

There is also a broader shift underway at NASA. Instead of massive, all-or-nothing missions, the agency is increasingly favouring smaller, faster, and more flexible projects that deliver results sooner and carry less financial risk.

The 'Invisible' Planet Wandering Alone Through Space

Astronomers have discovered a lonely planet drifting through the galaxy with no star to call home. It's being described as an "invisible" or rogue planet, and it's roughly twice the size of Earth. Unlike our planet, this world is travelling through deep space entirely on its own, after being violently kicked out of the planetary system where it was born.

The discovery was made by scientists in China using a clever combination of ground-based telescopes and the European Space Agency's Gaia space telescope. Gaia sits about 1.5 million kilometres from Earth, well beyond the Moon. By observing the same event from two very different locations, astronomers were able to pull off a kind of cosmic trick.

Here's how it worked.

The planet itself doesn't glow and reflects very little light, making it almost impossible to see directly. Instead, it revealed its presence by passing in front of a distant background star. As it moved across the star's line of sight, its gravity briefly bent and magnified the starlight — an effect predicted by Einstein called gravitational lensing.

Because Earth and Gaia were far apart, each saw the brightening of the star at slightly different times. That tiny difference allowed astronomers to calculate how massive the planet is and how far away it must be. It's a bit like judging the speed of a passing car by watching it from two different street corners. The result was surprising.

The object turned out to be about twice the size of Earth. That makes it a "super-Earth" — bigger than our planet, but much smaller than gas giants like Jupiter, which is more than 11 times Earth's width. This places the rogue world in an interesting middle ground that scientists are keen to understand better. What really caught researchers' attention, though, was its speed.

The planet is moving so fast that it almost certainly didn't leave its home system gently. Astronomers believe it was forcefully ejected, likely during a chaotic early period when young planets were jostling for position around their star. A close encounter with a much larger planet, or a passing star, could have flung it into interstellar space like a cosmic slingshot.

Once cast out, a rogue planet is condemned to eternal night. With no nearby star to warm it, its surface would be bitterly cold. Any atmosphere it once had may have frozen solid or been stripped away long ago. Even so, scientists think there could be billions of these wandering worlds drifting through the Milky Way — possibly outnumbering stars themselves.

This particular planet is not a threat to Earth and is still very far away. Its importance lies in what it tells us about how planetary systems form and, sometimes, fall apart.

Every discovery like this reminds us that the universe is far messier than the neat diagrams we see in textbooks. Planets can be born, battle for survival, and even be exiled — all without anyone noticing, until a faint flicker of distant starlight gives them away. Invisible, lonely, and on the run, this rogue planet is a powerful reminder that space is full of surprises, quietly racing past us in the dark.

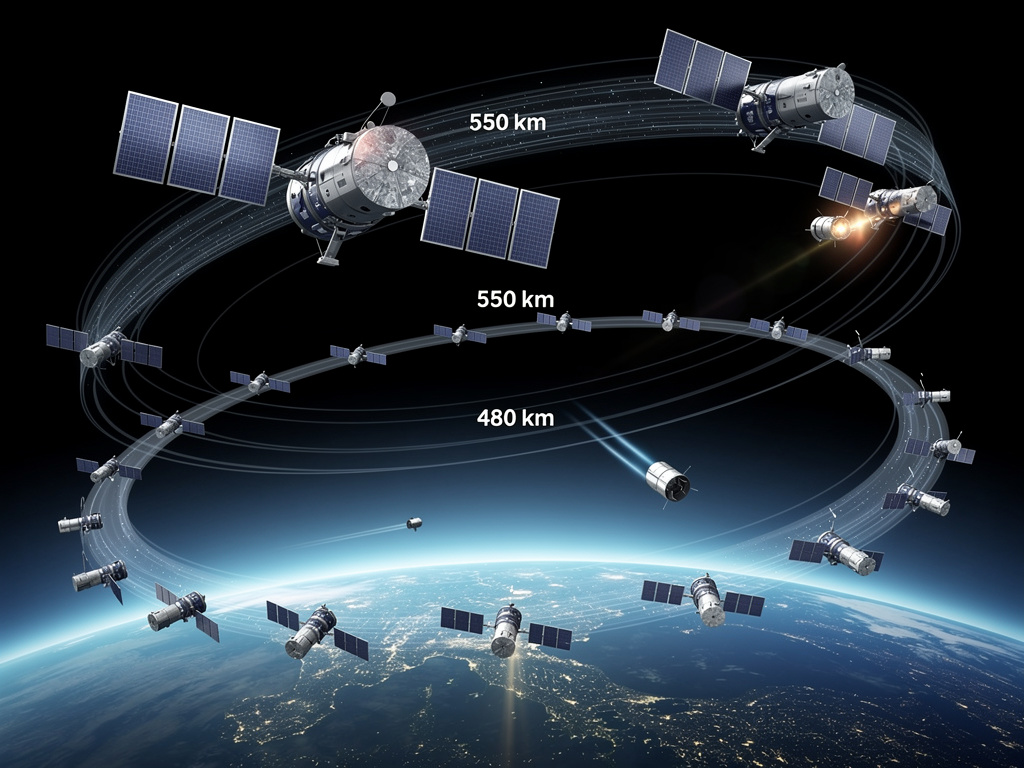

Starlink plans to lower satellite orbit to enhance safety in 2026

Starlink has announced plans to lower the operating altitude of thousands of its internet satellites in 2026, a move aimed at improving safety in an increasingly crowded region of space.

The satellites, which currently orbit Earth at around 550 kilometres, will be gradually moved down to about 480 kilometres. According to the company, this lower orbit reduces the risk of collisions with space debris and other satellites, while also ensuring that any malfunctioning spacecraft will fall back into Earth's atmosphere more quickly.

Low Earth orbit has become busier than ever, with many nations and companies launching large satellite constellations for communications, navigation and Earth observation. At orbital speeds of around 28,000 kilometres an hour, even small pieces of debris can cause serious damage. A single collision can create a cloud of fragments, increasing the danger for other spacecraft.

By operating at a lower altitude, Starlink says failed satellites will naturally burn up in the atmosphere within months, rather than remaining in orbit for years. The company says the change will affect roughly half of its current fleet and will be carried out gradually throughout 2026 to avoid service disruptions.

The decision follows growing global concern about space congestion and debris management. Industry experts see the move as a step toward more responsible use of Earth's orbital environment, as satellite numbers continue to rise.

Starlink says it is coordinating the orbital changes with space-tracking authorities to ensure the transition itself does not introduce new risks.

The First Footprint on Mars May Not Be Human

When SpaceX lands the first Starship on Mars, the most important passenger may not be an astronaut at all. It may be a machine.

Elon Musk has repeatedly said that Starship's purpose is Mars. Tesla has said Optimus exists to work where humans cannot or should not. Put those two trajectories together and a quietly radical idea emerges: the first "colonist" on Mars may be a humanoid robot, stepping down a ramp into red dust long before a human heartbeat ever does.

This is not science fiction. It is logistics.

Starship is designed to land heavy payloads on other worlds. Optimus is designed to manipulate tools, walk uneven terrain, lift objects, and learn tasks through AI training. Mars does not need a flag planted first; it needs infrastructure. Power, communications, shelters, resource extraction, repairs. Mars needs labour before it needs ceremony.

A robot does not need air, food, radiation shielding, or a return ticket. It does not panic. It does not suffer. It can fail, be rebooted, upgraded, replaced. That changes the entire risk equation of interplanetary exploration.

Picture the first Starship touching down in the thin Martian atmosphere. No dramatic voice crackling over a radio. No "one small step." Instead, a cargo bay opens. An Optimus robot walks down the ramp, its movements slightly stiff in lower gravity, its cameras adjusting to the amber sky. It pauses—not for awe, but for calibration.

Its job is simple at first: unload equipment, deploy solar arrays, connect cables, assemble antennas. Then more complex tasks follow: inspecting the Starship's heat shield for micro-damage, sealing joints against dust, erecting inflatable habitats, preparing landing zones for the next ships.

This is the unglamorous work that makes everything else possible.

Robots are particularly suited to Mars because Mars is hostile in ways that are tedious, not dramatic. Dust storms that last for weeks. Fine particles that clog mechanisms and lungs alike. Radiation that accumulates slowly, invisibly. Cold that seeps into everything. These conditions punish humans relentlessly but merely inconvenience machines.

Optimus does not need to be perfect. It does not need human-level intelligence. It needs to be "good enough" at physical tasks and capable of remote supervision from Earth or, eventually, from orbiting crews. Latency is not a dealbreaker; construction does not require conversation-speed responses. Much of the work can be scripted, rehearsed on Earth, then executed with adjustments.

Critics will say a humanoid robot is unnecessary, that wheeled rovers are more efficient. They are right—until you introduce tools, ladders, valves, handles, hatches, and equipment designed by humans for human bodies. A humanoid form is not about aesthetics; it is about compatibility. Optimus fits the world we already know how to build.

There is also a psychological dimension that should not be dismissed. When the first human crew finally arrives months or years later, they will not step into an empty wasteland. They will arrive at a place already worked by something that resembles them. A robot that walked the ground first, tested systems, left marks of activity. The difference between arriving at "nothing" and arriving at "something" matters to human morale more than engineers like to admit.

This approach also reframes exploration itself. We tend to imagine space as an extension of heroism—brave individuals risking everything. But the future of space may look more like supply chains, robotics, iteration, and redundancy. The romance fades, but the permanence increases.

There is a deeper provocation here: if machines can build a world before we arrive, what does it mean to be first? Is presence defined by biology, or by agency? If Optimus makes the first choices on Mars—where to place a shelter, how to orient a solar farm, which rock to move first—has Mars already been claimed by intelligence?

Perhaps that is the point. Mars does not need conquerors. It needs caretakers. And the first caretakers may be made of metal and code.

By the time humans finally stand on Mars, the planet may already bear the quiet fingerprints of Optimus—bolts tightened, panels aligned, pathways cleared. No footprint preserved in dust, but something more enduring: a functioning outpost.

History may record that humanity reached Mars not with a single giant leap, but with a careful, methodical walk—taken first by a robot sent ahead to make the impossible survivable.

And when that first human looks out across the Martian plain, they may not be alone. They may be greeted by a machine that has been waiting patiently, doing the work, long before anyone came to admire it.

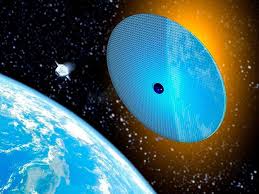

Turning Night Into Day? The Plan to Reflect Sunlight Back to Earth

Imagine stepping outside at night and seeing not just stars and the Moon, but a soft glow of sunlight coming down from space. It sounds like science fiction, but a California startup called Reflect Orbital wants to make it real.

The idea is surprisingly simple. Reflect Orbital plans to launch mirrored satellites into low Earth orbit. These satellites wouldn't create light of their own. Instead, they would act like giant space mirrors, bouncing sunlight back down to specific places on Earth after sunset.

Their first test satellite, named EARENDIL 1, is planned for launch in 2026. If that works, the company has much bigger ambitions. By 2030, Reflect Orbital hopes to have around 4,000 reflector satellites orbiting the planet.

So why would anyone want sunlight at night?

One major target is solar farms. Solar panels stop producing power once the Sun goes down. If reflected sunlight could extend daylight by even a short time, it could help generate extra electricity when demand is still high in the evening.

Another possible use is emergency services. During natural disasters like bushfires, floods, or earthquakes, reflected sunlight could provide temporary lighting over damaged areas, helping rescue crews work more safely and effectively when ground-based power systems are down.

The company also talks about supplying light to other paying customers, such as construction projects or remote locations that need illumination without building permanent infrastructure.

The satellites would orbit fairly close to Earth, which makes them easier to aim at specific locations. In theory, a mirror could be angled to briefly light up a chosen area, then move on. Reflect Orbital says this light would be controlled and targeted, not a constant glow.

Still, the idea raises big questions.

Astronomers are concerned about light pollution. Thousands of reflective objects in orbit could interfere with telescopes, making it harder to observe faint stars, galaxies, and asteroids. There are also worries about space traffic, as low Earth orbit is already crowded with satellites.

Then there's the human side. Night has always been dark for a reason. Wildlife, ecosystems, and even our own sleep cycles depend on natural darkness. Changing that, even locally, could have unintended effects.

For now, Reflect Orbital's plan remains experimental. The 2026 test mission will show whether the technology works at all. Whether it becomes a useful new tool—or an idea that proves too disruptive—will depend on what happens next. One thing is certain: the boundary between day and night may not be as fixed in the future as it has been for all of human history.

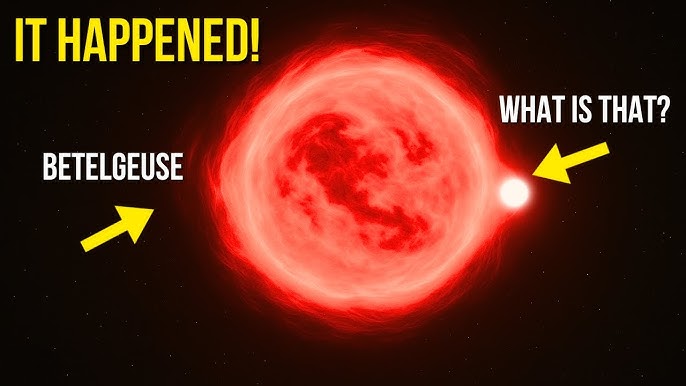

Betelgeuse Is Not Travelling Through Space Alone

Betelgeuse, the famous red star marking the shoulder of Orion, has long been thought of as a lonely giant drifting through the galaxy. New observations show that isn't quite true.

A research team from the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian has used the Hubble Space Telescope, along with powerful ground-based telescopes, to take a closer look at what surrounds Betelgeuse as it moves through space. What they found reveals a far busier environment than expected.

As Betelgeuse ploughs through the thin gas between the stars, it creates a vast bow shock—much like the wave that forms in front of a ship moving through water. This glowing arc of material sits ahead of the star in its direction of travel and shows that Betelgeuse is shedding gas into space while also pushing against its surroundings.

Even more intriguing, astronomers have found signs that Betelgeuse may have company. The data suggest the presence of a small companion star orbiting the red supergiant. This companion is far fainter and easily overwhelmed by Betelgeuse's brilliance, which explains why it escaped detection for so long.

If confirmed, this companion could help explain some of Betelgeuse's strange behaviour in recent years, including its famous dimming episode in 2019–2020, when the star unexpectedly faded and sparked worldwide speculation that it was about to explode as a supernova.

The surrounding arcs of gas and dust also tell a story of Betelgeuse's past. They appear to be leftovers from earlier mass-loss events, when the star threw off material as it evolved. These structures act like a cosmic footprint, marking where Betelgeuse has been and how it has changed over time.

None of this means Betelgeuse is about to explode tomorrow. While it will eventually end its life as a supernova, that event is still likely tens of thousands of years away.

What this research does show is that Betelgeuse is not an isolated wanderer. It is a massive, ageing star interacting with its environment—and possibly with a stellar companion—leaving clear evidence of its journey through the Milky Way.

Scientists capture a 10 Sec flash of light that reached Earth after a 13 billion year journey

Scientists have captured something extraordinary — a flash of light that lasted just ten seconds, yet had been travelling through space for 13 billion years before reaching Earth.

That brief blink was not small or ordinary. It was a powerful burst of energy released when the universe was still in its infancy. At the time this light began its journey, the universe was only a few hundred million years old. There was no Earth, no Sun, no Milky Way as we know it today. And yet, that ancient light survived everything the universe threw at it — expanding space, gravity, time itself — and finally arrived at our detectors here on Earth.

The flash appeared suddenly, shone intensely, and vanished almost as quickly as it came. In human terms, ten seconds is barely enough time to take a breath. In cosmic terms, it was a thunderclap from the distant past. Astronomers believe the flash came from one of the most violent events in the universe. These bursts are created when massive stars collapse at the end of their lives, or when ultra-dense objects like neutron stars collide. For a moment, they can shine brighter than entire galaxies.

What makes this event truly breathtaking is its distance. The light set off on its journey more than 13 billion years ago, when the universe was young and just beginning to form its first stars and galaxies. By the time it reached Earth, it had crossed almost the entire observable universe. This single flash gives scientists a rare glimpse into the universe's earliest chapters. It acts like a time machine, allowing astronomers to study conditions from a time long before planets, oceans, or life existed.

Moments like this remind us how powerful modern astronomy has become. We are no longer just looking out into space — we are looking back in time, catching whispers from the dawn of everything. A ten-second flash. A thirteen-billion-year journey. And a quiet reminder that the universe still has plenty of wonders left to reveal.

Tractor beams inspired by sci-fi are real, and could solve the looming space junk problem

Imagine tractor beams — the invisible pulling forces made famous by science fiction — but real. Not the dramatic movie kind, but a practical version that could help solve one of spaceflight's biggest problems: space junk. Scientists are now working on real tractor beam technology, and it could become an important tool for cleaning up Earth's crowded orbit.

The growing space junk problem

Earth is surrounded by thousands of dead satellites, broken rocket parts and fragments from past collisions. These objects race around the planet at enormous speeds. Even something the size of a bolt can punch a hole in a working satellite.

In 2009, two satellites collided, creating more than 1,800 pieces of debris. That single accident made space more dangerous for everyone and added to a growing problem that gets worse every year. If left unchecked, space junk could make some orbits unusable for future missions.

A tractor beam that really works

Engineers at the University of Colorado Boulder are developing something called an electrostatic tractor. It sounds futuristic, but it's based on well-known physics.

Here's how it would work:

A servicing spacecraft approaches a dead satellite but never touches it. The spacecraft fires a gentle stream of electrons toward the old satellite, giving it a negative electric charge. At the same time, the servicing craft becomes positively charged.

Because opposite charges attract, the two objects become linked by an invisible electric force. From dozens of metres away, the servicing spacecraft can slowly and carefully pull the dead satellite along with it. The movement would be very slow, taking weeks, but that's the point. Slow and steady means safe.

Why this approach is clever

Most space-junk removal ideas involve grabbing, pushing or attaching cables to dead satellites. That's risky. One wrong move and a satellite could break apart, creating even more debris. The tractor beam idea avoids contact completely. Nothing is touched. Nothing is squeezed. That greatly reduces the chance of creating new junk.

Once captured, the dead satellite could be moved into a "graveyard orbit," safely away from busy space lanes used by communications, weather and GPS satellites. Experts say the idea is realistic and promising, even though it still needs more testing.

What happens next?

The biggest challenge is funding. Building and launching a working space tractor won't be cheap. Engineers estimate it could take several million dollars and about a decade to go from concept to a working mission.

Even so, the idea marks a major shift. Something that once lived only in science fiction is now being seriously designed by scientists who want to protect Earth's space environment. Tractor beams may not look dramatic, but if they work, they could quietly help keep space open, safe and usable for generations to come.

Famous 'Wow!' signal received by SETI from deep space was even stronger than once believed

On the night of August 15, 1977, something extraordinary happened. A radio telescope known as Big Ear, operated by Ohio State University, was quietly scanning the sky when it detected a signal so powerful and unexpected that it instantly stood out from the background noise of space. The signal lasted just 72 seconds.

When astronomer Jerry Ehman examined the computer printout, he circled the strange data and wrote one word in red ink beside it: "Wow!" That simple reaction would give the signal its name and begin one of the longest-running mysteries in modern astronomy.

The signal did not behave like ordinary cosmic noise. It was unusually strong, tightly confined to a very narrow frequency, and astonishingly clean. Most natural radio sources spread their energy across a wide range of frequencies. This one did not. It looked focused, deliberate, and precise — exactly the sort of pattern scientists associate with technology rather than nature.

Even its location added to the intrigue. The signal appeared to come from the direction of the constellation Sagittarius, close to the centre of the Milky Way, a crowded and complex region of the galaxy filled with stars, gas and unknowns.

Then there was the frequency itself....The Wow! signal arrived at 1420 megahertz, the natural radio emission frequency of hydrogen, the most abundant element in the universe. For years, scientists involved in the search for extraterrestrial intelligence had suggested this would be the logical "universal channel" for any advanced civilisation trying to announce its presence. Hydrogen is everywhere. The frequency is quiet. The symbolism is hard to miss.

For decades, the signal was described as powerful but brief. However, more recent re-examinations of the original data have revealed something even more unsettling. When researchers carefully accounted for how Big Ear's antenna scanned the sky, they realised the signal was likely stronger than originally believed. Much stronger. If the signal came from far beyond our solar system, as the data suggests, it would have required an enormous amount of energy to transmit. Not something easily produced by random cosmic processes.

Over the years, many explanations have been proposed. One of the most popular blamed passing comets, but that idea has largely fallen apart. The suggested comets were not in the correct position at the time, and more importantly, comets do not produce narrow, sharply defined radio signals like this one. Nature is usually messy. This signal was not.

Equipment malfunction was also considered, yet the signal's structure does not match known faults or interference. It rose and fell exactly as expected for a real source moving through the telescope's field of view. Perhaps the most haunting detail of all is this: The Wow! signal was never detected again. Scientists returned to the same patch of sky repeatedly over the years. They listened. They waited. They searched. ....Nothing.

No repeat transmission.

No follow-up signal.

No explanation.

Nearly half a century later, the Wow! signal remains officially unexplained. It has never been confirmed as alien in origin, yet no natural cause has been conclusively identified either. It remains a single, powerful moment when the universe seemed to clear its throat, speak once — very loudly — and then fall silent. And that small red-ink note, written in a moment of disbelief, still captures the mystery better than any technical report ever could: Wow.

NASA's planned return to the Moon under the Artemis program is far more than a symbolic

NASA's planned return to the Moon under the Artemis program is far more than a symbolic revisit to a familiar destination. It represents a fundamental shift in how humanity explores space—and why. Under the emerging leadership vision outlined by Jared Isaacman, the return mission is being framed as the start of a permanent human foothold beyond Earth, not a one-off achievement.

The first crewed landing of the Artemis era, Artemis III, will mark the first time humans walk on the Moon since 1972. But unlike Apollo, the goal is not to arrive, collect samples, and leave. Artemis astronauts are expected to land near the Moon's south pole, a region never visited by humans and one of the most scientifically intriguing places in the inner solar system. Permanently shadowed craters there are believed to hold water ice—an invaluable resource that can be turned into drinking water, breathable oxygen, and even rocket fuel.

This return mission is designed to test whether humans can operate sustainably on another world. Astronauts will live on the lunar surface for longer periods than any previous Moon mission, relying on advanced spacesuits, surface power systems, and a new generation of lunar landers built by commercial partners. Every step, from landing precision to surface mobility, is aimed at answering one question: can we stay?

The Artemis return also marks a strategic change in how NASA works. Rather than building everything in-house, the agency is acting as architect and referee, setting goals while industry provides much of the hardware. The Space Launch System and Orion spacecraft will carry crews to lunar orbit, while privately built landers ferry them to the surface. This layered approach spreads risk and accelerates innovation, but it also means Artemis is a test of partnership as much as engineering.

What truly sets this return apart is what follows. Artemis III is intended to be the beginning of a sequence, not a climax. Subsequent missions will build toward a sustained presence, including surface habitats, power stations, and eventually a lunar outpost. The Moon becomes a training ground for Mars, allowing engineers and astronauts to practice living far from Earth, with long communication delays, limited resupply, and real consequences for failure.

In that sense, the return mission is a turning point. Apollo proved we could reach the Moon. Artemis aims to prove we can learn from it, use it, and build there. If successful, this return will be remembered not as a nostalgic echo of the past, but as the moment humanity began extending its reach permanently beyond Earth.

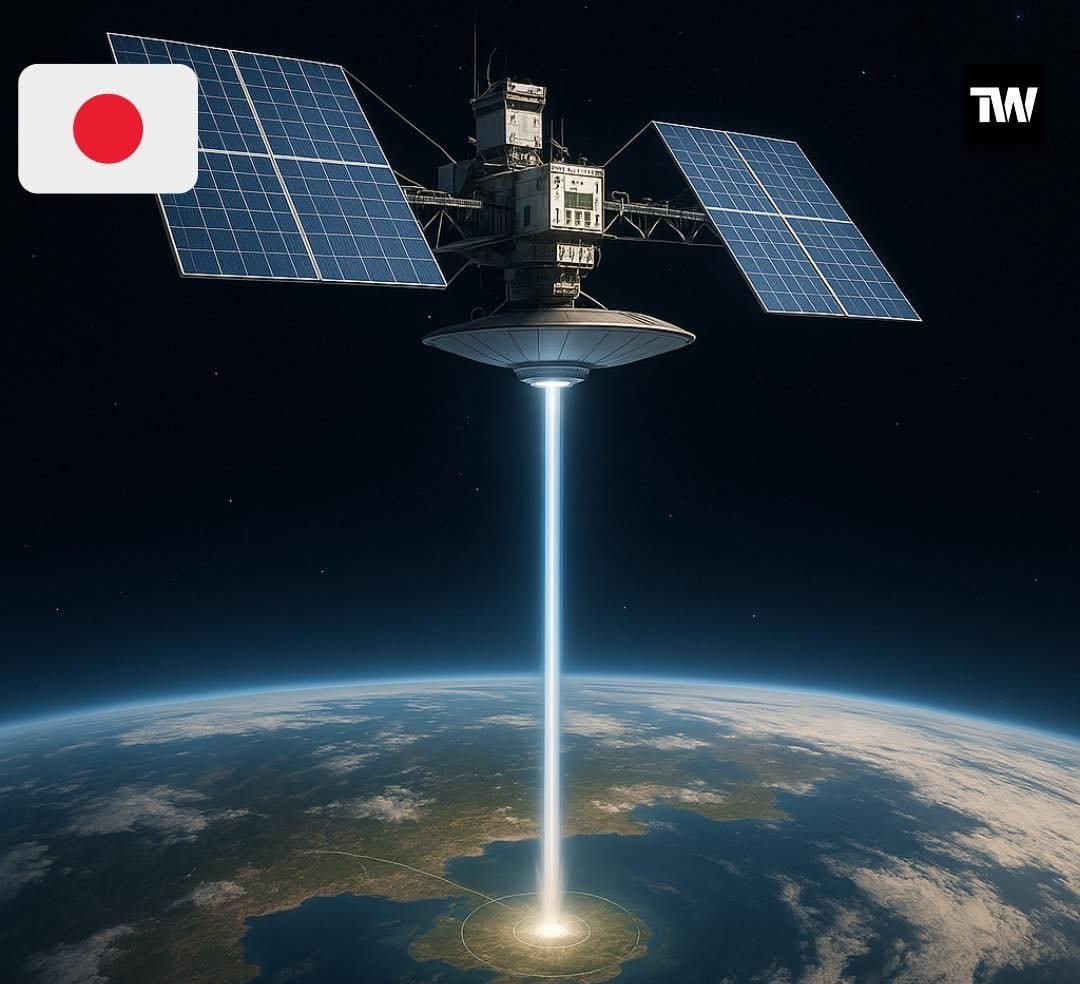

Japan Is Making History by Harnessing Solar Power From Space

High above Earth, where sunrise comes every 90 minutes and clouds are irrelevant, Japan is preparing to attempt something no nation has ever done before. In 2025, a small satellite named OHISAMA — the Japanese word for "the Sun" — will be launched into low Earth orbit, about 400 kilometres above the planet. It won't make headlines with astronauts or fiery launches. Its mission is quieter, but potentially far more profound.

Once in orbit, OHISAMA will unfurl its solar panels and begin collecting unfiltered sunlight — energy that never switches off, unaffected by night, weather, or seasons. Instead of storing that power onboard, the satellite will convert the electricity into microwaves and transmit it directly back to Earth.

The beam will be aimed at a receiving station near Suwa, Japan. If all goes to plan — with orbital timing, alignment and beam precision working perfectly — roughly one kilowatt of power will reach the ground. That's enough to boil a kettle, power a television, or run a small office. By modern energy standards, it's modest. But history rarely announces itself with volume.

What matters is that this would be the first successful transmission of usable solar power from space to Earth. A demonstration that a long-imagined idea can finally move from theory to reality. The concept of space-based solar power dates back to the 1960s, when engineers first realised that sunlight in orbit is constant and intense — roughly ten times stronger than what reaches Earth's surface. Capture it in space, beam it down, and the planet's energy problems suddenly look very different.

For decades, the idea remained impractical. Launch costs were enormous. Solar panels were heavy and inefficient. Beam-control technology lacked precision. Safety concerns lingered. The dream stayed on paper.

OHISAMA is deliberately small because it is designed to answer the hardest questions first. Can energy be transmitted accurately from orbit? Can the beam be controlled safely through the atmosphere? Can such a system survive the harsh realities of space? If the answers are yes, the future becomes strikingly clear.

Scaled-up versions would not be single satellites, but kilometre-wide orbital power stations, delivering continuous energy day and night, rain or shine. No fuel. No emissions. No dependence on geography. Any location with a receiver could draw clean power from above — cities, islands, remote regions, even disaster zones.

There are still formidable challenges ahead. Launching and assembling space power stations remains expensive. Long-term safety must be proven beyond doubt. International agreements will matter. This is not an overnight solution. But every revolution begins with a test. In 2025, when a faint microwave beam touches down in Suwa carrying energy collected in orbit, it will mark a subtle but historic shift — the moment humanity begins to see space not just as something to explore, but as something that can power the world.

The Sun has always powered Earth. Japan is about to show we can collect it — from space itself.

The $4.3 billion space telescope Trump tried to cancel is now complete

For a telescope that nearly didn't exist, NASA's Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope has arrived in remarkably good shape. After years of political brinkmanship, budget skirmishes, pandemic delays, and multiple attempts at cancellation under the first Donald Trump administration, the $4.3-billion observatory is now fully assembled, tested, and quietly waiting for launch as soon as late 2026. In an era where big science projects often stumble dramatically, Roman's story is notable not for chaos — but for how little of it there was. That alone makes it unusual.

Roman, named after NASA's first chief astronomer, was completed inside a vast clean room at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland. Its core has survived violent acoustic tests, rocket-level shaking, and the thermal extremes of a vacuum chamber designed to mimic space itself. On November 25, engineers joined its inner and outer sections, formally declaring the observatory complete. For NASA, that's a rare sentence to say out loud without crossing fingers.

Part of Roman's smooth path comes from what it is not. Unlike the James Webb Space Telescope — a mechanical origami nightmare with more than 300 single points of failure — Roman avoids elaborate deployments. There will be no multi-stage sunshield ballet, no segmented mirrors unfolding a million miles from Earth. A protective aperture door opens. Solar arrays deploy. The telescope gets to work. Engineers describe the risks as "normal aerospace risks," which in NASA language is about as close to calm as it gets.

Roman's primary mirror is 2.4 metres across, the same size as the Hubble Space Telescope. Conveniently, it didn't even need to be built. The mirror was donated by the US National Reconnaissance Office, originally intended for a spy satellite that was never flown. The gift removed one of the riskiest steps in telescope construction, though it required a larger spacecraft and a heavier rocket — likely a SpaceX Falcon Heavy. If Webb is about seeing deeper than ever before, Roman is about seeing more.

Its Wide Field Instrument contains 18 infrared detectors, each 4,096 by 4,096 pixels, forming a 300-megapixel camera — the largest infrared focal plane ever assembled. By comparison, Hubble's near-infrared camera uses a single 1,024-pixel detector. The difference is transformative. Roman can match the sharpness of Hubble's famous Ultra Deep Field, but across an area of sky at least 100 times larger.

In practical terms, Roman will survey in months what would take Hubble centuries. One planned program will cover in nine months what Hubble would need up to 2,000 years to complete. Another will map the equivalent of 3,455 full moons in just three weeks, then repeatedly revisit part of that region to track motion and change.

That's where the speculation begins. Roman isn't just taking pictures — it's building time-lapse cinema. Astronomers expect to create genuine 3D movies of the Milky Way and distant galaxies, watching stars drift, clusters shear, and gravity subtly sculpt cosmic structures. This is statistical astronomy at industrial scale, aimed squarely at dark matter and dark energy, which together make up roughly 95 percent of the Universe.

Roman also carries a coronagraph, a high-contrast instrument designed to block starlight and reveal faint nearby worlds. It should image planets up to 100 million times fainter than their host stars, performing 100 to 1,000 times better than similar instruments on Webb or Hubble. Combined with Roman's wide-field planet-hunting surveys, scientists expect it to discover more than 100,000 exoplanets in its first five years.

Big numbers matter. Patterns only emerge when samples are enormous. Roman's data torrent may finally reveal whether dark energy is constant, evolving — or a sign that gravity itself is incomplete.

Politically, Roman's survival is almost as interesting as its science. Congress repeatedly restored funding after proposed cancellations, even with Trump back in office and renewed budget pressure in 2026. Unlike Webb, Roman stayed under a strict cost cap, ending up about $300 million over its original estimate, largely due to pandemic disruptions.

Perhaps that discipline explains why, during testing, engineers found no torn membranes, no loose screws, and no cascading surprises. For a NASA flagship mission, that borders on uncanny. If Webb taught us how the first galaxies lit up, Roman may show us how the Universe moves, breathes, and bends. It won't steal Webb's spotlight — but it may quietly redraw the map underneath it.

How Long Will The Footprints On The Moon Last?

In July 1969, when Buzz Aldrin pressed his boot into the Moon's dusty surface, he didn't just leave a footprint. He left a quiet rebuttal to every doubter who would ever claim it didn't happen.

More than half a century later, that footprint is still there. Not a softened outline. Not a blurred memory. The same crisp impression Aldrin photographed beside the Apollo 11 Lunar Module. On Earth, a footprint lasts minutes before wind, rain, or the next passer-by wipes it away. On the Moon, time plays by very different rules.

The Moon has no atmosphere. That means no wind to scatter dust, no rain to wash it smooth, no rivers, no waves, and no weather of any kind. It is a world locked in near-permanent stillness. Once something disturbs the surface, it tends to stay disturbed. Geological activity is minimal. There are moonquakes, but they are weak and infrequent. Erosion, as we understand it on Earth, simply doesn't exist.

So how long will those footprints last? The honest answer is astonishing: potentially millions of years. The only real threat comes from micrometeorites — tiny grains of space debris that pepper the lunar surface at high speed. Over immense spans of time, these microscopic impacts will gradually soften edges and blur shapes. But "gradually" is the key word. At the current rate, the Apollo footprints could remain recognisable longer than human civilisation has existed so far.

The rippled shapes seen around those footprints tell an interesting story of their own. Lunar soil, called regolith, is nothing like Earth dirt. It's made of crushed rock and glassy fragments created by billions of years of impacts. There's no moisture to bind it together, yet the grains are sharp and angular, so they interlock when pressed. When an astronaut stepped down, the weight compressed the soil unevenly, forcing it outward in tiny ridges and waves. Those ripples aren't decorative — they're a physical record of pressure, motion, and human presence in a place that had never known either.

Sceptics sometimes scoff, asking why the flag doesn't wave or why the footprints look "too perfect." The irony is delicious. The very things they point to as suspicious are exactly what physics predicts in an airless world. No wind means no waving. No erosion means perfect preservation. The Moon isn't hiding the evidence — it's protecting it.

There's something deeply human about those marks. Astronauts later admitted they sometimes walked backward just to avoid stepping on earlier footprints, aware they were altering a surface untouched for billions of years. On Apollo 17, Gene Cernan even traced his daughter's initials into the dust, knowing they might outlast every monument on Earth.

Since 1972, no human has returned. The footprints remain undisturbed, sitting in total silence under a black sky. One day, new explorers will stand beside them again. When they do, they won't just be looking at old boot prints. They'll be standing face to face with proof of a triumph — a moment when a small, fragile species reached across space and left a mark that time itself has chosen not to erase.

In this day and age, it's staggering some still claim the Moon landing was faked. We have laser reflectors, tracked missions, and crystal-clear images from NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter. Anyone can visit the LRO website and see the Apollo landing sites—footprints, tracks, and all.

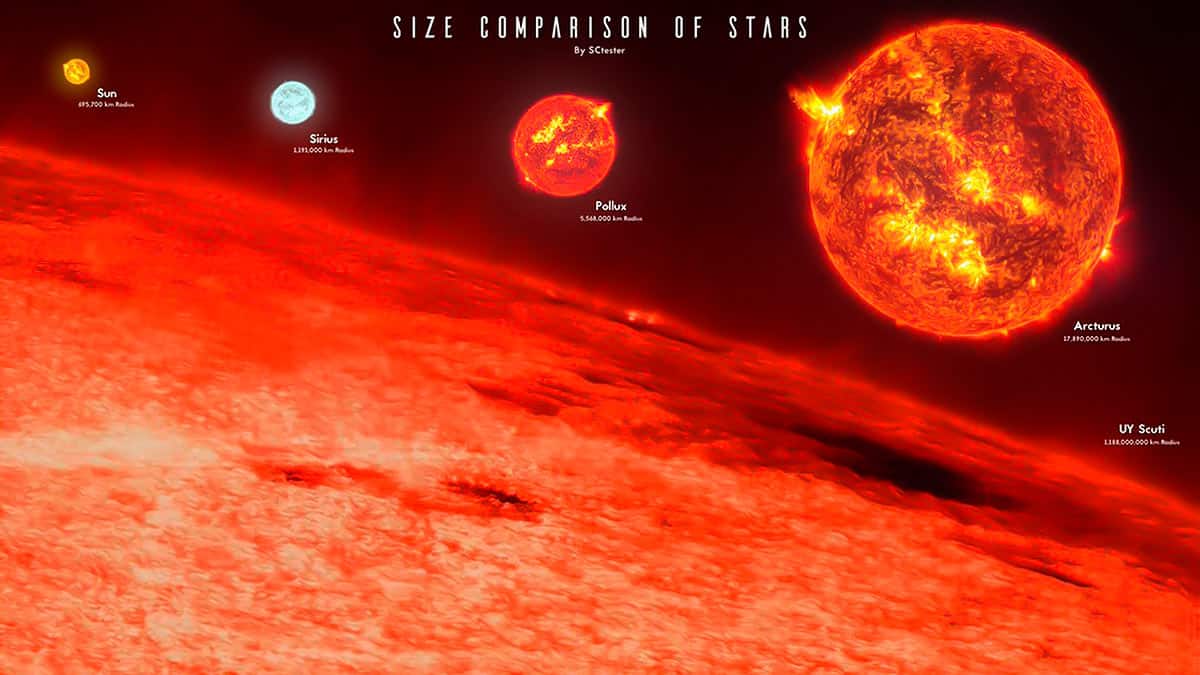

The Biggest Star in the Universe 10 Billion Times Bigger Than Our Sun

Some stars shine quietly for billions of years and fade away without much fuss. Stephenson 2-18 is not one of them. This is a star that seems almost too big to exist — a cosmic rule-breaker that stretches our understanding of how the universe works.

Stephenson 2-18 is a red supergiant, one of the largest types of stars ever discovered. To call it "large" is wildly inadequate. If this monster replaced our Sun, it would balloon outward so far that it would swallow Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, and even Saturn. The space where our entire solar system now peacefully orbits would instead be a churning ocean of glowing gas.

The scale is staggering. Light, the fastest thing in the universe, would take more than eight hours just to cross from one side of Stephenson 2-18 to the other. For comparison, light crosses our Sun in seconds and reaches Earth in eight minutes. Suddenly, the Sun — the engine of all life on Earth — looks almost embarrassingly small. Next to Stephenson 2-18, it would resemble a grain of dust floating beside a blazing bonfire.

But size alone doesn't tell the whole story. Stephenson 2-18 is unstable, restless, and living on borrowed time. Red supergiants are stars in their final chapter, bloated and exhausted after burning through their nuclear fuel at a furious pace. Stephenson 2-18 is shedding enormous amounts of material into space, blowing off stellar winds so vast they could one day seed future star systems.

Some astronomers think it may already be wobbling on the edge of collapse. Inside its core, nuclear reactions are stacking heavier and heavier elements, like a cosmic game of Jenga. Eventually, the structure can no longer support itself. When that happens, the result could be one of the most violent events in the universe.

One possibility is a supernova — an explosion so powerful it briefly outshines entire galaxies. In that single moment, Stephenson 2-18 could release more energy than our Sun will produce over its entire lifetime. For weeks or months, it would blaze across the Milky Way, visible across vast interstellar distances.

The other possibility is even stranger. The star may collapse directly into a black hole, with little warning and no dramatic explosion — simply vanishing, leaving behind a region of space where gravity reigns supreme and light itself cannot escape. A giant disappearing without a bang, as if the universe quietly erased one of its largest creations.

What makes Stephenson 2-18 even more fascinating is how rare such stars are. Objects this large live fast and die young. While stars like our Sun enjoy lifespans of around ten billion years, Stephenson 2-18 may burn out in just a few million. In cosmic terms, it is a mayfly — massive, brilliant, and fleeting.

Located about 19,000 light-years away, this stellar titan is safely distant from Earth. Its eventual death won't threaten our planet, but it does offer astronomers a priceless glimpse into the extremes of nature. Stars like this forge the heavy elements that eventually become planets, oceans, and even life itself. Iron in your blood and calcium in your bones were born in ancient stellar deaths not unlike the one Stephenson 2-18 is heading toward.

In the end, Stephenson 2-18 is more than just a giant star. It is a reminder that the universe doesn't just build things on a human scale — it builds them with outrageous ambition. It shows us that reality can be far stranger, bigger, and more dramatic than imagination ever dared to be.

Somewhere out there, a colossal star is burning furiously, shedding its outer layers, and edging closer to a spectacular finale. And when that final moment comes, the universe will once again remind us just how small we really are — and how astonishing the cosmos can be.

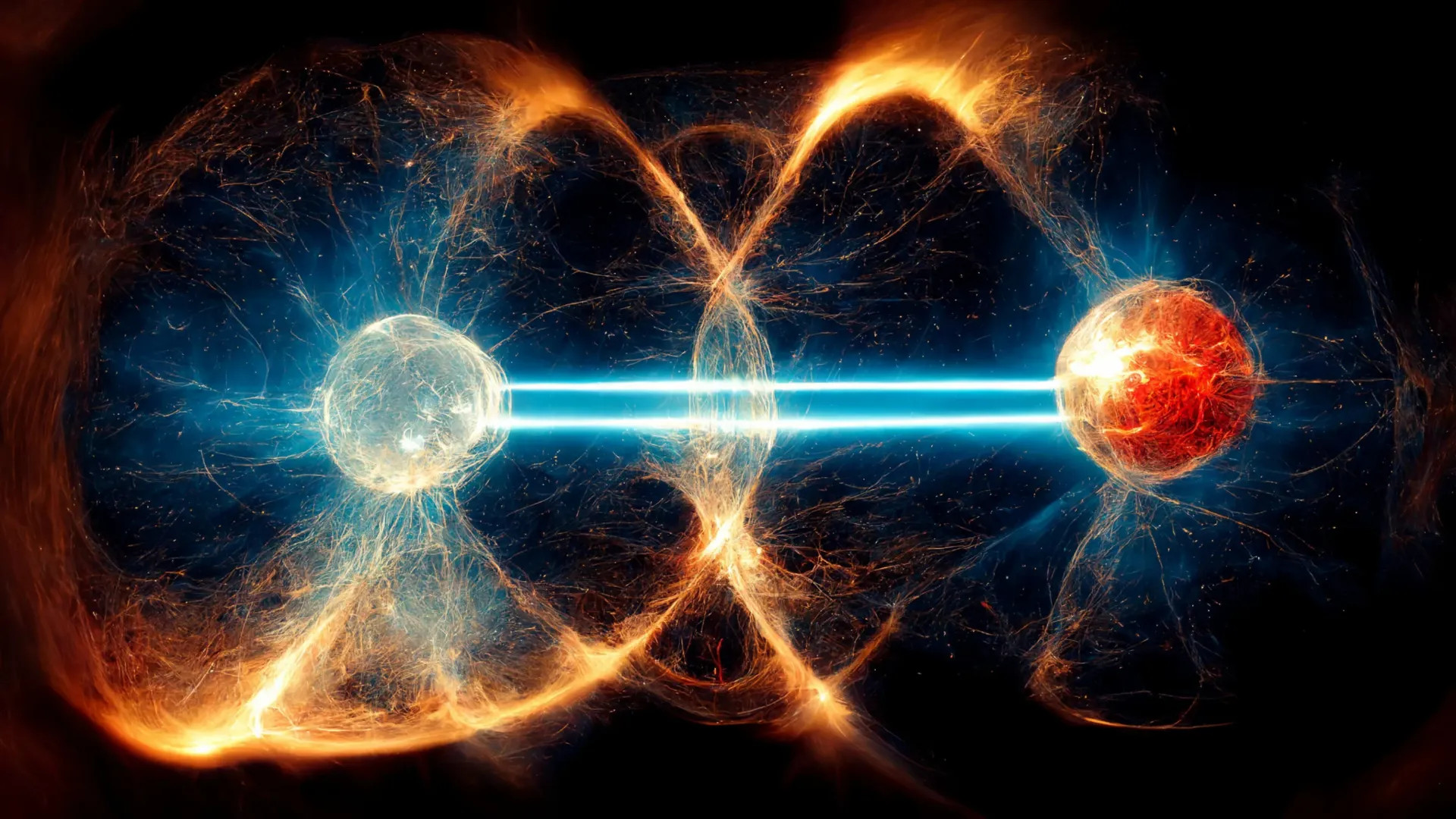

Quantum Entanglement and the Coming Age of Teleportation

An easy-to-grasp look at the science that may reshape human travel

THIS may be the most incredible/amazing story you have ever read: Quantum entanglement sits at the heart of some of the most fascinating work in modern physics. It's an idea so strange that even Einstein raised an eyebrow at it, famously calling it "spooky action at a distance." Yet despite the nickname, the phenomenon is very real. If two tiny particles become entangled, they behave as one system no matter how far apart they travel. Change something about one, and its partner reacts instantly—even if one is in Sydney and the other could somehow be waiting on Mars.

Picture a magical pair of coins. Flip one, and the other immediately shows the same result. Not because a message rushed between them, but because, in a sense, they share the same identity. That, in a nutshell, is quantum entanglement: a silent connection built into the very structure of reality. This invisible link is now guiding scientists toward ideas that were once reserved for science-fiction writers, including the headline act—teleportation.

Teleportation today isn't about moving objects from A to B. Instead, scientists use entanglement to transfer the state or properties of one particle to another somewhere else. It's a bit like copying a document, except the original version disappears the moment the new one appears. This technique has been tested repeatedly in laboratories, between mountaintops, across cities, and even between Earth and satellites.

Turning this into a method for moving physical objects—and ultimately people—is enormously more complicated. A human being is made of unimaginable numbers of particles. Teleporting someone would require capturing the exact state of every one of those particles and sending that information elsewhere to be rebuilt perfectly. That's equivalent to mapping every grain of sand on an entire beach with flawless accuracy, then recreating that beach grain-by-grain somewhere else.

We're nowhere near that level of precision yet, but history shows that "impossible" is often just a temporary label.

Some far-reaching theories suggest that the fabric of space itself can be bent, twisted, or folded. If that's true, then distant locations might be linked through tunnels or shortcuts sometimes described as "holes." They aren't holes in the usual sense but distortions in spacetime that connect two places directly—much like folding a sheet of paper so two dots that were far apart suddenly touch.

Quantum entanglement appears in several of these theoretical models. Researchers suspect it could help detect, measure, or perhaps even stabilise these spacetime shortcuts. At the moment, these ideas live largely in mathematical equations, but they hint at a future where teleportation doesn't just transmit information. It could move physical matter—and potentially living passengers—through controlled gateways formed by the structure of the universe itself.

How the Technology Might Evolve

A realistic but forward-looking path for the development of quantum teleportation could look like this:

2025–2040

-

Major progress in quantum computers.

-

Routine teleportation of information between ground stations and satellites.

-

First solid theoretical models describing tiny, short-lived quantum "space holes."

2040–2060

-

Controlled teleportation of simple matter—atoms and small molecules.

-

Spacecraft adopt quantum-linked systems for instant communication.

-

Early attempts to stabilise microscopic spacetime shortcuts.

2060–2100

-

Teleporting complex objects becomes possible on a laboratory scale.

-

Quantum holes remain stable long enough for tiny probes to traverse.

-

Global agencies explore long-range, no-rocket material transport.

22nd century and beyond

-

Full object teleportation becomes practical.

-

Human teleportation, if proven safe, appears in extremely restricted trials.

-

Space travel shifts dramatically as teleportation hubs replace launch pads.

-

A network of quantum "highways" turns the solar system into a familiar neighbourhood. The Future in One Sentence

Quantum entanglement is the universe's built-in communication thread, and if humanity learns to master it, teleportation—of data, objects, and eventually people—could transform travel from a physical journey into a simple step between two points in space.

**Leave a message or comments on this website Email me directly : www.davereneke@gmail.com

NB/ Please Include Your Name and Email address If You Require An Answer.

'ASTRO DAVE' RENEKE - A Personal Perspective

His extensive background includes teaching astronomy at the college level, being a featured speaker at astronomy conventions across Australia, and contributing as a science correspondent for both ABC and commercial radio stations. David's weekly radio interviews, reaching around 3 million listeners, cover the latest developments in astronomy and space exploration.

As a media personality, David's presence extends to regional, national, and international TV, with appearances on prominent platforms such as Good Morning America, American MSNBC news, the BBC, and Sky News in Australia. His own radio program has earned him major Australasian awards for outstanding service.

David is recognized for his engaging and unique style of presenting astronomy and space discovery, having entertained and educated large audiences throughout Australia. In addition to his presentations, he produces educational materials for beginners and runs a popular radio program in Hastings, NSW, with a substantial following and multiple awards for his radio presentations.

In 2004, David initiated the 'Astronomy Outreach' program, touring primary and secondary schools in NSW to provide an interactive astronomy and space education experience. Sponsored by Tasco Australia, Austar, and Discovery Science channel, the program donated telescopes and grants to schools during a special tour in 2009, contributing to the promotion of astronomy education in Australia. David Reneke, a highly regarded Australian amateur astronomer and lecturer with over 50 years of experience, has established himself as a prominent figure in the field of astronomy. With affiliations to leading global astronomical institutions,

David serves as the Editor for Australia's Astro-Space News Magazine and has previously held key editorial roles with Sky & Space Magazine and Australasian Science magazine.